On exhibition at the GEDOK Brandenburg Kunstflügel Gallery as part of the Dialog:Linie 2 Zeichnung & Resonanz exhibition

2. – 26.October 2025

curated by Kaj Osteroth

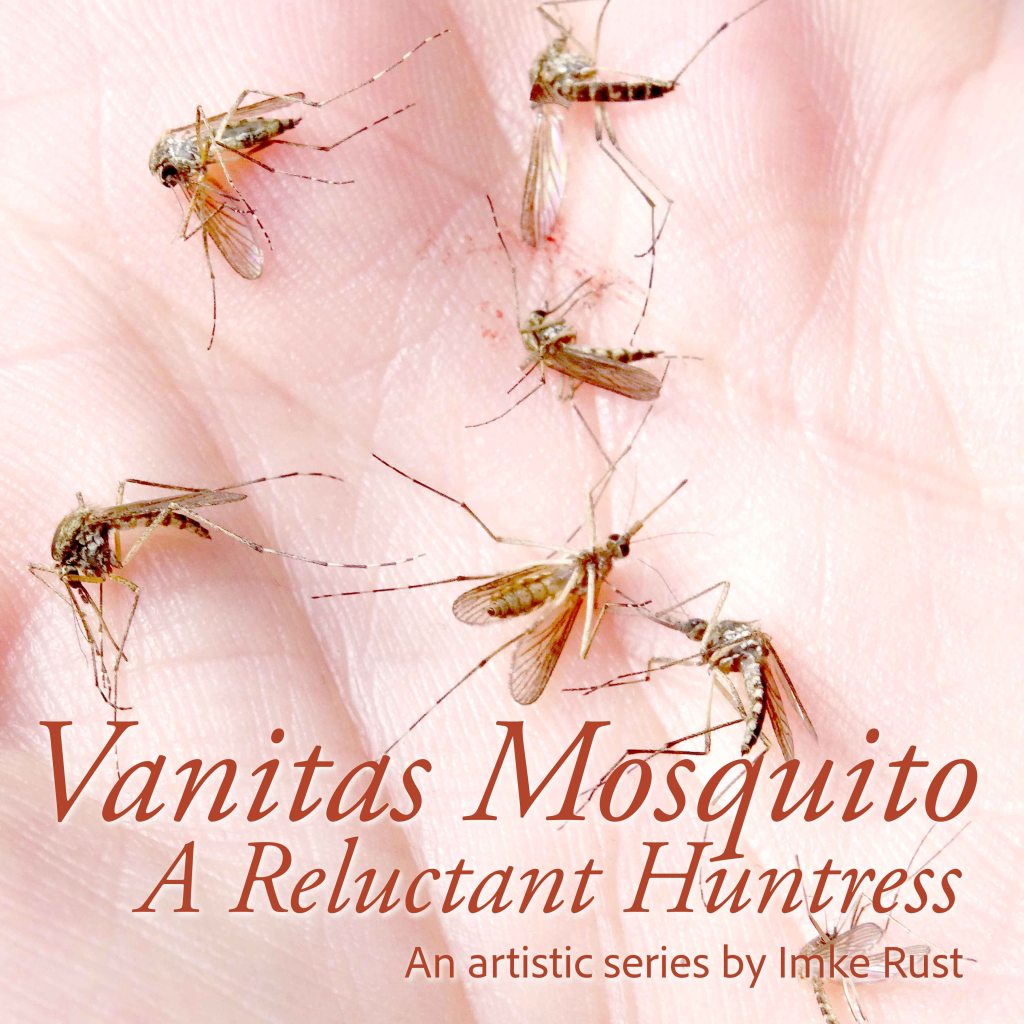

With Vanitas Mosquito – A Reluctant Huntress, I turned my encounters with mosquitoes into a poetic inquiry into the relationship between humans, nature, and violence.

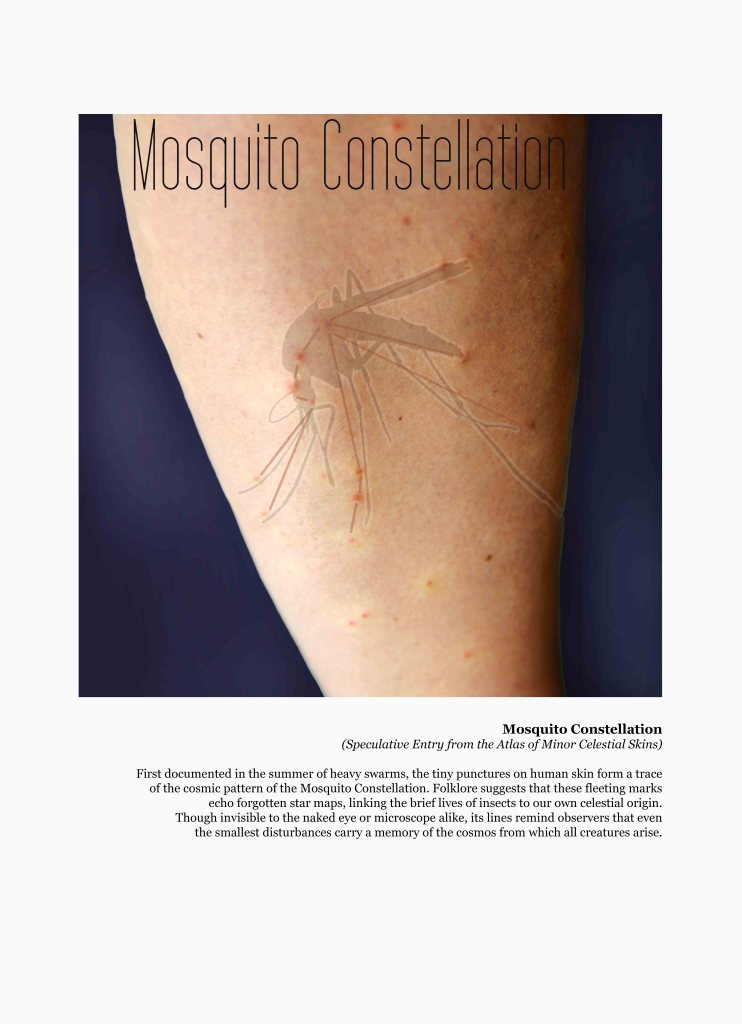

What began as an irritating summer problem (in 2017) becomes an artistic investigation: in the Mosquito Collection, dead insects are archived meticulously; in Mosquitoes Rehearse Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, their bodies draw the notes of a silent, macabre serenade. Blood drawings of oversized mosquitoes reflect guilt, the shifting roles of victim and hunter, and the paradox of a creature so saturated with the artist’s own blood that it becomes partly her; while imaginary “X-rays” and the Mosquito Constellation weave pain, body, and cosmos together.

The series reflects the tension between defense and intimacy, between protection, beauty, and destruction. It raises questions about the ethics of killing — even when done for self-protection — and about our place within a web that connects all life.

Art historically, the project moves between conceptual art, body art, and ecological philosophy. It combines the precision of an archive with the radicality of bodily materials and the openness of a poetics of nature. Vanitas Mosquito is thus less a work about mosquitoes than a meditation on coexistence: on how every act of separation remains, at the same time, a gesture of belonging.

Vanitas Mosquito – A Reluctant Huntress

This body of work begins with something seemingly banal: a summer full of mosquitoes, sleepless nights, itchy welts on the skin, and the reflexive act of killing just to find some rest. But instead of forgetting this cycle of irritation and defense, the artist transforms these moments into a complex visual diary — one that dissects, and at the same time poetizes, the tangled relationship between humans, nature, and violence.

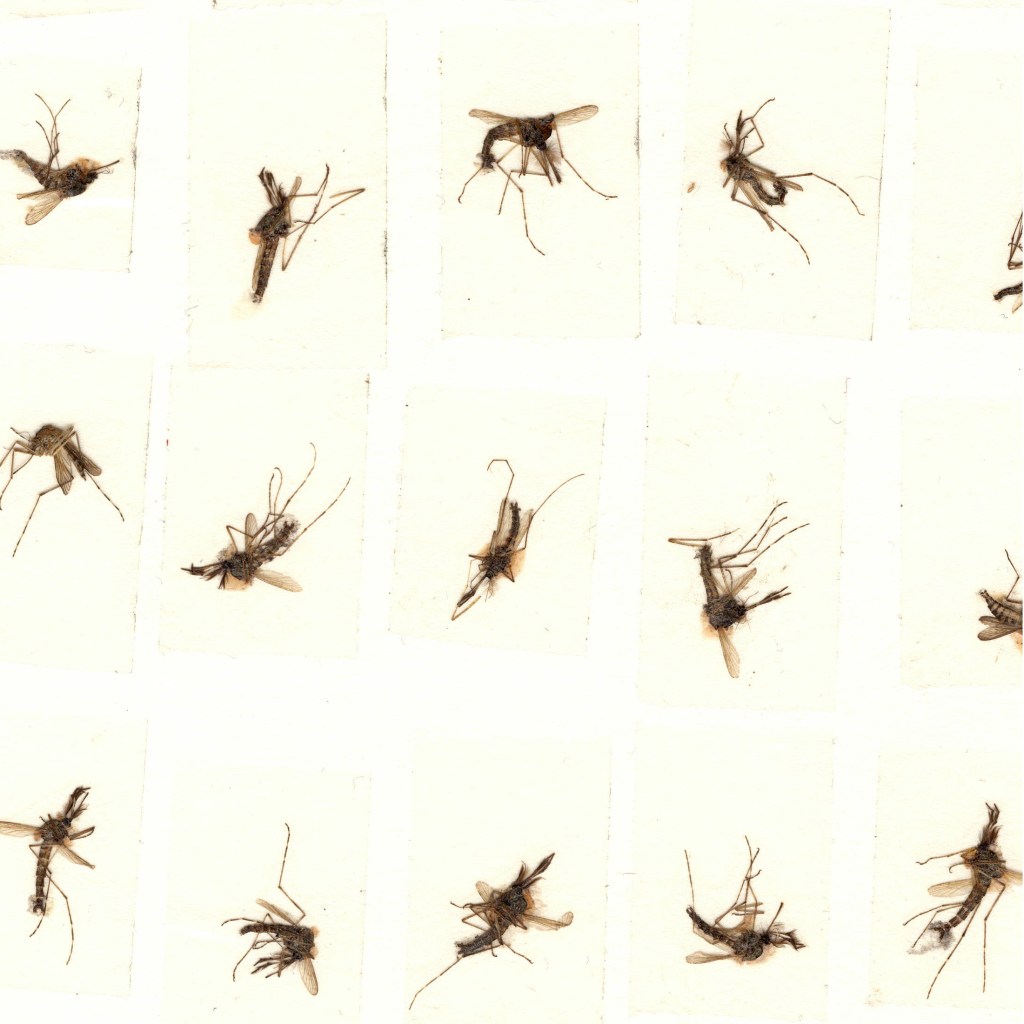

The Mosquito Collection, with the insects lined up meticulously on strips of tape, recalls both a natural history archive and a forensic investigation. Yet beneath the strict order lies another truth: a quiet acknowledgment of the ambivalence between protection and destruction, between action and guilt. Each preserved mosquito is not merely a remnant but a testament to that contradictory tension of closeness and rejection.

This tension becomes especially vivid in “Mücken proben Eine kleine Nachtmusik” (Mosquitoes rehearse Eine kleine Nachtmusik): here, the artist arranges dead mosquitoes as notes on a sheet of Mozart’s famous serenade. What was once an unbearable, droning sound in the night becomes a silent, macabre score. The work oscillates between humor and melancholy — between the irony of turning irritation into aesthetic order and the quiet sadness that only death could silence the noise.

The blood drawings of oversized mosquitoes push this conflict further. Here, the mosquito becomes a trophy, an icon, drawn with the artist’s own blood — the same blood that once gave life to those tiny bodies. It is a paradoxical play of victim and perpetrator, of intimacy and glorification. These works pose uncomfortable questions: Is aesthetic transformation a form of justification? Or does it simply reveal how deeply we are entangled in a cycle of violence and connection?

A critical undercurrent emerges when thinking about the logic of trophy hunting — the urge to make the killed visible, to mark control or victory. But here that logic is turned on its head: the “reluctant huntress” celebrates no conquest; she instead reflects on her own role in a process she can neither fully embrace nor entirely avoid.

Other works open a broader horizon. The imagined “x-ray scans,” forming skull-like anatomies from countless mosquito bodies, evoke something archetypal and mythic — as if these insects were more than mere pests, but carriers of a deeper, almost universal presence. In Mosquito Constellation, the artist maps the bites on her own skin into the outline of a celestial figure, transforming traces of pain into a cartography of something larger — a reminder that even injury belongs to the same web that connects all living things.

This perspective echoes ecological philosophies such as those of Andreas Weber, which seek the “thou” in every living being, or spiritual ideas like those in Conversations with God, in which all life emerges from a single source. The series thus quietly asks: if everything is one — human, mosquito, blood, night — how does that change the way we view the act of killing, even when it feels like self-defense?

Art historically, the series sits between conceptual art, body-based practices, and contemporary ecological discourse. It references the clinical precision of scientific archiving, the radical intimacy of 1970s body art, and the poetic openness of a nature philosophy that no longer separates human and non-human.

In the end, the work offers no easy answers, only a field of tensions: between defense and intimacy, guilt and beauty, the individual and the whole. Vanitas Mosquito is therefore not only a series about mosquitoes, but about the paradox of coexistence — in a world where every act of separation is also, inevitably, an act of connection.